Extracted Wealth

Our History of Deficits

The national debt is on track to become the largest single annual federal expenditure in the United States. The growing cost of servicing this debt places increasing pressure on economic planning and limits the government’s ability to fund future priorities. As this burden accelerates, it is vital to understand not only why it continues to grow, but also what must be done to help reverse this trend.

The national debt is the cumulative total of federal budget deficits. Each year that the government spends more than it collects in tax revenue, the difference is added to the debt. Although occasional deficits are normal in recessionary periods or wartime, persistent deficits are structurally different. In the last century, the U.S. budget has been balanced only a handful of times, signaling that the drivers of debt are not temporary, but systemic.

At its core, a deficit has only two causes: government either spends more than it collects or collects too little for what it commits in spending. Because the federal budget includes baseline obligations—Social Security, Medicare, national defense, infrastructure, disaster relief—and because financial insecurity persists for millions of Americans, it is difficult to claim that the government is generously overspending on its citizens. The other side of the equation, national tax revenue, therefore warrants closer examination.

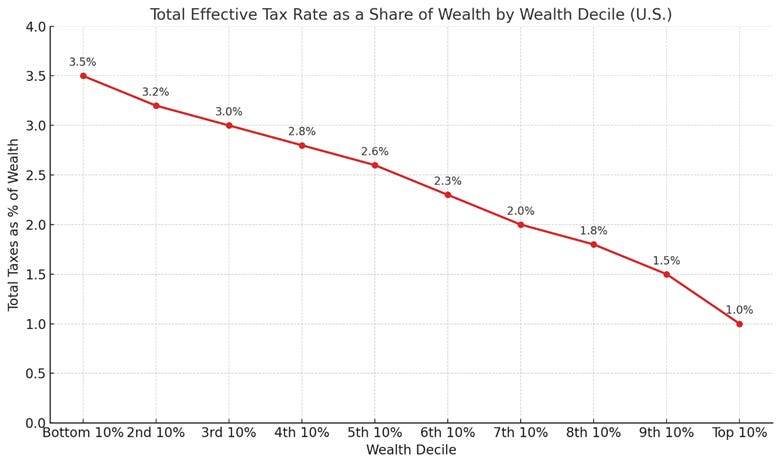

A critical but underexamined reality is where the tax burden fails to keep pace with relative wealth. Almost all nations of the world have some form of progressive taxation where a higher tax rate is imposed on higher income earners. This accepted principle loses its value when taxes are measured not as a percentage of income but as a percentage of accumulated wealth as the following graph shows.

The top 10% of households pay roughly 1% of their total wealth per year in federal taxes

The bottom 10% pay approximately 3.5% of their wealth annually

This disparity is driven by the layers of regressive taxation all wage earners are required to pay. Payroll taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, excise taxes (gasoline, tobacco, and alcoholic beverages), and state and local fees are forms of regressive taxation that fall hardest on wage earners. These taxes are more significant as a share of household resources at the lower end of the wealth distribution, making the U.S. tax system effectively regressive when viewed through the lens of wealth, not income.

If tax fairness is to be the assumption, then the current tax structure not only fails but guarantees persistent deficits. In the current tax regime, no attempt has been made to consider all levels of taxation and the ability to pay. The issue is not that the federal income tax code is not progressive, the issue is that the federal tax code is not progressive enough to offset the regressive nature of all other forms of taxes and fees that income earners must pay.

This also has consequences beyond the budget. Extreme wealth concentration does not merely reshape markets—it reshapes political power. Today, segments of the ultra-wealthy openly question the value of democratic governance, suggesting that “expert-managed systems”, insulated from public demand and democratic friction, could govern more efficiently. Their immense financial leverage gives this argument reach, even when unpopular in principle.

To solve the chronic deficits problem that limits national options we must question a tax system that asks proportionally more of those who have less while deferring revenue from where wealth has concentrated most. Until we address both the arithmetic of revenue and the architecture of fairness, the United States will struggle not only to balance its books, but also to preserve the democratic foundations that make self-government possible.

Excellent piece, John. It's succinct and well articulated. I'm going to share it with others. I'd like to suggest that you submit it to Letters to the Editor at the Post or another national newspaper.